In our third and last installment of reading famous American photographs, we cover Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima, the February 23, 1945 photo by Joe Rosenthal showing five U.S. Marines and a Navy corpsman raising the flag on Mount Suribachi, the highest point of the Japanese island of Iwo Jima:

Rarely does a photograph convey urgency and movement as fully as this. The effort of the man on the right to physically plant the flag pole into what looks like difficult, hard ground is clear. His head is turned down, looking at the ground, focused on his work. The next man to the left is also focused on training the pole into the ground. The man behind him pushes the pole upward, and the last man has just lost his grip on the pole as it raises. His arms still strain upward with the force of his effort. The wind is just about to unfurl the flag, signifying victory. Yet for all the movement, the men also seem made of marble—it looks very much like a sculpture. The perfect triangle composition that takes your eye from the flag down the pole to the man planting it, across to the men holding the pole, and back up to the flag is classic. There is nothing in the sky to distract from the lone symbol of the flag—no airplanes, no shells exploding.

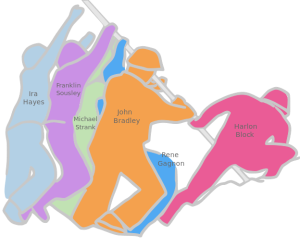

The first question might be, why are there only four men? Unfortunately, one man is almost completely blocked from view behind the second man from the right because their bodies were lined up as they both worked to plant the flagpole. Here’s a helpful diagram:

This outline also gives us the men’s names. Franklin Sousey, Michael Strank, and Harlon Block would all be killed in the Battle of Iwo Jima: Stank and Block on March 1, within hours of each other, and Sousley on March 21, just days before the official end of the Battle on March 26, 1945.

The Battle of Iwo Jima was critical to the U.S. war effort in the Pacific. It was the first Japanese home island to be invaded by the U.S. in its “island-hopping” strategy of taking the small but strategic Pacific islands the Japanese relied on to refuel planes on their way to bigger targets. Often these islands were so small that they were uninhabited. But each island the U.S. landed on was defended to the death by the Japanese, who knew that a) they needed these islands as stopping points to faraway destinations and b) that the Americans were slowly but surely working their way to invading Japan itself. When U.S. forces invaded Iwo Jima on February 19, 1945, they were met with even fiercer resistance than before.

The Americans wanted to capture Mount Suribachi as soon as possible so the Japanese could not use it as a lookout and a place from which to shell incoming U.S. forces. It was taken relatively quickly, on February 23, just four days into the battle. But the fighting was far from over, as the Japanese barricaded themselves into pillboxes dug into the hillsides and fired on U.S. forces for another unbelievably fatal month.

There were actually two different flag-raisings on Mount Suribachi. The first was ordered by Lt. Col. Chandler Johnson and sent Harold Schrier, Earnest Thomas, and Henry Hansen up the mountain with a 40-man combat patrol. Johnson is said to have given Schrier a flag and said “If you get to the top put it up.” Schrier did, and received a Navy Cross for volunteering for the mission. A photographer named Louis Lowry who joined the patrol took photos of this first flag-raising.

The sight of the flag so inspired the Secretary of the Navy, James Forrestal, who was at Iwo Jima, to say “the raising of that flag on Suribachi means a Marine Corps for the next five hundred years.” According to legend, he asked General Holland Smith if he could have it as a souvenir. This reportedly enraged Lt. Col. Johnson, who felt the flag belonged to his battalion. To keep it away from Forrestal, Johnson ordered another group up the mountain to replace it. This was not the only reason, of course; Johnson wouldn’t endanger his men in such a petty mission. They needed to put up a bigger flag that could be seen better by men on the landing beaches. And so the second, famous group went up about two hours after the first group. They had been laying telephone wire on Mount Suribachi during the first flag raising. Joe Rosenthal took his photo and history was made. But he almost missed it; while he was setting up for a good shot, the men began raising the flag, and Rosenthal had to grab his camera to get a shot before it was over. As Rosenthal took photos, Sgt. Bill Genaust shot newsreel footage of the event. (Genaust was killed on March 4.)

When Rosenthal sent his film to Guam to be developed, the AP photograph editor immediately spotted the shot and sent it to New York. The photo was printed in hundreds of newspapers in less than 24 hours. It spoke to the bravery of the U.S. armed forces, the pride of the U.S. victory at Iwo Jima, and the danger Americans were facing in the Pacific theater.

But then trouble began. Rosenthal asked the men to pose for a group photo after the flag-raising. When he was asked a few days later if his photo was posed, he said yes—not knowing the questioner was referring to the already-famous flag-raising photo and not the group shot. Word spread that the photo was a fake. The popular New York radio program Time Views the News claimed that “Rosenthal climbed Suribachi after the flag had already been planted… Like most photographers he could not resist reposing his characters in historic fashion.” The Pulitzer Prize the photo had already won was threatened with revocation. When he realized the error, Rosenthal went to his grave defending the photo. Genaust’s newsreel film proved that Rosenthal’s shot was really from the flag-raising as it happened, and most people realized it was not fake, but for decades the conspiracy theory persisted in the shadows—growing up in the 1970s, one of us at the HP remembers hearing it was faked, and accepting this claim without much ado, as children do. Hopefully by now, that rumor is finally dead.

In honor of the other U.S. servicemen who risked their lives to plant the flag, we give you a photo of the first flag-raising on Mount Suribachi:

There’s not the same immediate energy as the more famous photo, but this image does capture the grim resolution of the men. As the flag is steadied in its plant, one man in the center sits down, seemingly exhausted, eyes on the horizon. One man stands looking in the same direction, perhaps at the U.S. forces continuing to land on the beaches below, for whom the flag is a signal that Japanese shells will no longer rain down on them from the peak. The mountain is captured, the flag is raised, but the battle is not over, and even as the photographer faces the men, the soldier closest to him keeps a lookout inland for Japanese fire. The moment is not as technicolor as the more famous photo, but the bravery and commitment are just as real.

War is a fascinating subject. Despite the dubious morality of using violence to achieve personal or political aims. It remains that conflict has been used to do just that throughout recorded history.

Your article is very well done, a good read.

LikeLike