Hello and welcome to part the last of our short series on Radio and the Great Debate over U.S. Involvement in World War II, by Mark S. Byrnes. As we said in part 1, Mark painstakingly documents the many Americans who made their cases for the intervention and anti-intervention sides of the argument between September 1939 and December 6, 1941, when the Japanese attack on the U.S. Navy at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii settled the question.

His main focus is disproving the established anti-interventionist (“isolationist”) claim that the interventionists got special treatment–more time on the air, and support from a Democratic-controlled Congress that did whatever the popular and clearly interventionist Democratic president, Franklin Roosevelt, said to do. Both sides got equal time, and both sides made points that resonated with Americans.

In part 1 we covered the first argument in the anti-interventionist side of the debate: the wishful thinking Americans engaged in that the war could be won without them. In part 2, we looked at the second, even more alarming argument against going to war: that the U.S. could get along just fine–even thrive–in a world where fascism had conquered Europe and Asia.

Now we conclude with the final, fainter argument made most explicitly by the American Socialists who entered the debate. Not faint because it was presented timidly, but because it was a more complex argument than the overall “it is our business–no it’s none of our business” debate generally encouraged.

In April 1941, author Stanley High, of the FFF (a recently formed pro-intervention organization), debated Norman Thomas, chair of the Socialist Party. Stanley presented the stark choice: “Either Hitler’s defeat is of desperate, deadly importance to us or it’s of no importance whatsoever.” He believed it was of desperate importance, and that America should enter the war as a belligerent, not just send aid to allies. He concluded his opening statement by saying “We can either beat Hitler now–or we can deliver into his hands the power to fashion our future.” (273)

Norman Thomas didn’t disagree on the main point–he agreed that Hitler and fascism were a threat. Where he took issue was on that last idea that fighting and defeating Hitler would make sure fascism did not dictate America’s future.

Norman said that entering the war with the honest intention of defeating fascism would, in fact, dictate that fascism rose to power in America: “I believe that we should go not so far as to insure the triumphs of an American Hitlerism, and that would be the probably consequence of our entry into total war.” (273)

His point was that fighting fascism on three continents would require a mobilization of people, industry, government, and society unparalleled in U.S.–or perhaps even human–history. The U.S. would have to fundamentally change all four to make the turn on a dime that would be entering a war that was already in full swing. Government would have to be given new powers to take over industry, which would mean mobilizing people as workers, turning over food production to the war effort, food rationing, and a complete halt to the manufacture of cars and appliances for private use. Trains, the main means of long-distance transportation in the country, would be reserved for transporting soldiers, other war personnel, raw materials, and finished war goods. Government spending would skyrocket while wages dropped.

To do all of this, the federal government would expand almost beyond reckoning, and that’s what Norman and the Socialists feared. As Mark puts it, Norman “feared that the result of a total war effort would be an irreversible centralization of power that would threaten American liberty. Total war, [Norman] argued, ‘will require us to lose our internal democracy for the duration.'”

He was likely remembering WWI, when freedom of speech was basically thrown out the window by the federal Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918. These Acts basically made it illegal to criticize the U.S. government or the war effort by giving a wide, ever-changeable definition of espionage and sedition. The “Red Scare” immediately after the war was used as a reason to prosecute American citizens charged with being Communists. The Sedition Act was repealed in 1920, but the Espionage Act was still in force. The scaffolding was already in place on which fascism could be erected in the U.S.

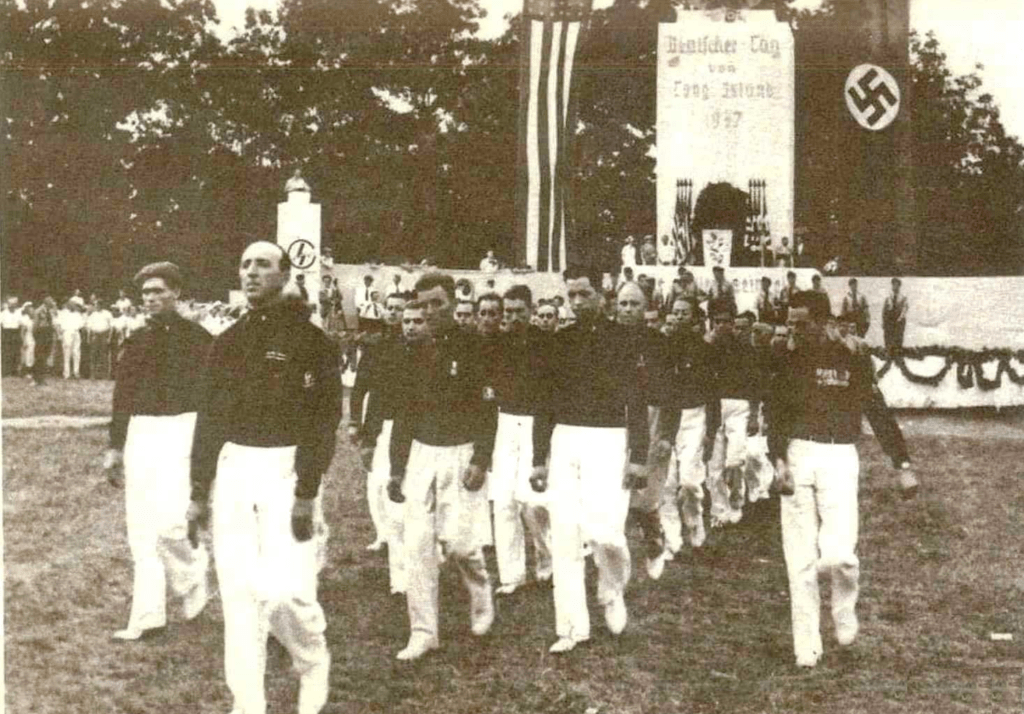

American Nazis existed, and they had grown louder and more unashamed as the crimes of the Nazis in Europe unfolded in the late 1930s. You can see a good documentary of the American Nazis (the “German American Bund” as they called themselves) of that time at PBS: Nazi Town, USA. The town of Yaphank, New York, on Long Island, was one of their strongholds, and Nazi youth camps, called “Camp Siegfried”, operated in five states. This is a photo from the Camp Siegfried in Yaphank:

American Nazis were a minority of the population. But German Nazis were, too, yet they were able to take over their government and country. If the U.S. expanded the federal government and stripped state and local governments of some of their power in order to mobilize for the war, and passed acts to eviscerate freedom of speech, this would open the door to American Nazis. Even if the U.S. won the war against fascism abroad, it would lose the war to fascism at home.

And if the U.S. won the war at a moment when it had its troops all over the globe, would it be willing to withdraw those troops? or would it seize the opportunity to expand its own empire?

And if the U.S. won the war, would it really return industry back to private, commercial manufacture? Or would the federal government continue to massively fund the military, in the name of preventing another war, but in reality to protect the new lands it now controlled?

And if the U.S. won the war, would it really restore full civil rights to its citizens? or would it continue to curb them in order to squash protest against the imperial expansion and the military spending?

“The primary consequence [of a U.S. victory] would be ‘an American… imperialism which would perpetuate armaments, and for which Fascism at home in this generation must be the inevitable accompaniment,” Norman warned. As Mark sums it up, for Norman Thomas and the Socialists, “War was, in every possible scenario, a no-win proposition.” (273-4)

Their argument was overshadowed at the time, and easy to dismiss in the years immediately after the war, when the U.S. seemed to indeed reverse all its wartime emergencies and return to normal. But the key word there is seemed. The American Nazis officially disbanded, and the Nazi youth camps shut down. Industry returned to commercial production and spawned the boom of consumerism that made the 1950s and 60s a high-water mark of personal and household purchasing. The Civil Rights movement was revived in the 1950s and won huge gains in the 1960s, including desegregation and voting rights.

But this is not the whole story. Those American Nazis closed their camps, but they didn’t go away. They lived on to pass down their hatred to their next generation, to wave Confederate flags at lynchings, and threaten, torture, and kill Civil Rights activists. Industry created out-of-control consumerism but not at the expense of military production. Military production continued apace with the excuse of the Cold War. The U.S. went into permanent wartime military spending, and military spending is still by far the largest slice of the federal budget pie to this day.

In 1961, outgoing president Dwight Eisenhower warned Americans that all was not well. In his farewell address he coined the phrase “the military-industrial complex”:

A vital element in keeping the peace is our military establishment. Our arms must be might, ready for instant action, so that no potential aggressor may be tempted to risk his own destruction. . . . American makers of plowshares could, with time and as required, make swords as well. But now we can no longer risk emergency improvisation of national defense; we have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions. . . . This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. . . .Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. . . . In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.

Dwight Eisenhower was proven to be as prescient in 1961 as Norman Thomas had been twenty years earlier in 1941. The U.S. government and military have been involved in other nations’ governments since the war, carrying out crimes and terrorism when needed to meet U.S. interests. Our military power was impossible to walk away from, especially with the Cold War providing a constant justification for imperialism in the name of promoting democracy. The influence of unchecked military and industrial spending is seen in the very innovation that drove consumerism from the start–constant new inventions, new technology, from microwave ovens to computers to the Internet to cell phones. Many commercial products have their origin in military experimentation. More dangerously, the invisibility of the people who control our destiny that began with the top-secret Manhattan Project that created atomic bombs continues, as a small group of people, mostly white men, develop AI without any guardrails or intervention, oversight, or control from outside.

Finally, all the money that the military-industrial complex generates has corrupted our government at every level, as lobbyists, kickbacks, and insider trading demonstrate over and over.

America still struggles to achieve full democracy, but it is, in the end, an always-difficult fight that has indeed been made much more difficult by our victory in World War II. This is not to say we should not have entered the war. Of course we had to, and should have done it sooner.

What it is to say is that American democracy would be in much better shape if Americans had cared to intervene in European and Asian politics in the 1920s, after the first world war had enriched America and devastated many European nations as well as Japan. Rather than accept that wealth as deserved, the U.S. could have used it to level the playing field, support democracy at home and abroad, and used the Paris Peace Conference to really change the status quo, rather than consolidate its own gains. Then there may not have been a WWII to consider entering into.

Such “what if” history is usually frowned upon, but it’s worth considering. It’s no more wishful thinking than the idea that America really did emerge from the total war effort unscathed.