It shouldn’t be necessary to parse such a short text to fully comprehend its meaning; it shouldn’t even really be possible. But the Gettysburg Address, delivered on November 19, 1863 at the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by President Abraham Lincoln, packs a great deal of meaning into a very few words, and the fact that some of its phrases have become iconic, used liberally in everyday society, has actually blurred some of their meaning. Let’s go through it, attempting to be as concise as the author was, but knowing we will fail [this article is many times longer than his speech]:

“Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

—Yes, the first five words may be the most well-known; there’s probably no American alive today over the age of 5 who hasn’t heard those words, usually used in jest, or presented as impenetrable. It’s the one archaic rhetorical flourish Lincoln included. “Score” means 20, so the number is four times 20 plus seven, or 87 years ago. In 1863, that was, of course, 1776, the year the Declaration of Independence was written and signed.

The important thing about that number and that date is how recent it was; just 87 years ago there had been no United States. Adults in the crowd at Gettysburg had heard their parents’ stories about colonial days, and the Revolutionary War. Their grandparents might never have known independence. So the nation brought forth so recently, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal, possessed all the vulnerability of youth. It was not a powerful entity that could be counted on to withstand a civil war, particularly one that amassed casualties such as those at the Battle of Gettysburg.

“Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated can long endure.”

—The point is reiterated: can the U.S. survive the war? But Lincoln’s real question is about the precarious state of world affairs that the U.S. Civil War represented. The U.S. was founded as a nation dedicated to liberty for all. The Confederacy that fought the war was fighting for slavery, the opposite of liberty, and there seemed to be a real possibility that other nations, primarily England and France, would join the war on the Confederate side. If the Union lost the war, the only attempt at real democracy, personal liberty, and equality on Earth would be no more, and there might never be another. The U.S. had the best chance at making it work; if the U.S. failed, who could succeed? The worst fears of the Founders and of all patriotic Americans were realized in this war, and in losses like the ones at Gettysburg.

“We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.”

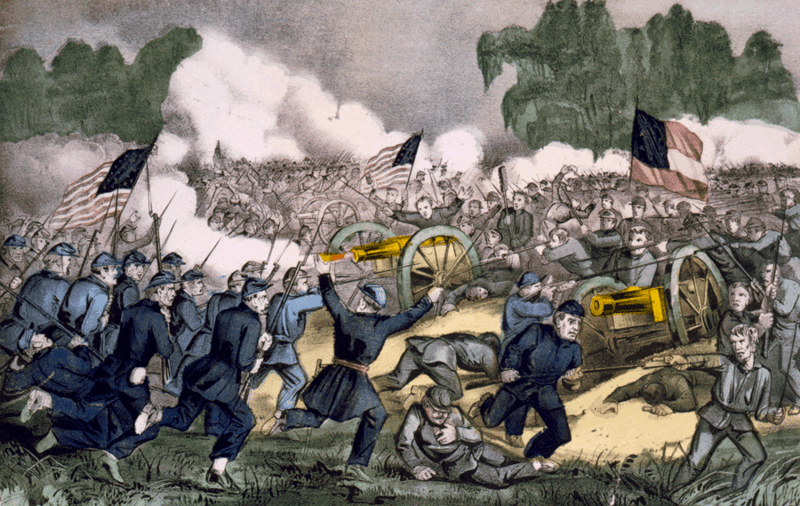

—This was a recent battlefield. The bodies were cleared away, but the landscape was devastated by three days of cannon and gunfire. This drawing purports to show the start of the battle:

The soldiers are in a field surrounded by trees. Here is a photo from the day of the Address:

Yes, it’s now November instead of July, but the ground being completely stripped of vegetation is not the result of the onset of winter, and the lack of a single tree speaks volumes about the ferocity of the battle. There is a tree stump taken from the battlefield at Spotsylvania on display at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, DC that is all that’s left of a tall tree that was shot away to nothing by rifle fire during the fighting.

Gettysburg’s trees must have suffered the same fate. Under that stripped-bare ground many men from both sides were already hastily buried. There was a strong need on the part of the families of the dead, who could not travel to Pennsylvania to find and retrieve their bodies, to find some way to set this battlefield aside as sacred ground.

“But in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead who struggled here have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.”

—You can make the battlefield into a cemetery, but that action is not what makes the field sacred. It is the unselfish sacrifice of the dead, who fought to keep democracy and liberty alive in the world, that makes the land sacred—not just the land of the cemetery, but all lands of the United States. They are buried now in the cemetery, but they will live forever in the memory of the nation.

“It is for us the living rather to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced.”

—The “unfinished work” the soldiers were doing is the work of keeping democracy alive as well as the nation.

“It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—”

—“The last full measure of devotion” must be one of the most powerful ways to say “they gave their lives” ever conceived of. The men buried here did not just die for a cause, they died because their faith in liberty was so devout that they put the life of their nation above their own lives.

“—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation under God shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth.”

—We tend to think that the last phrase, “government of the people, by the people, for the people”, must have appeared somewhere before this, in the Constitution or some Revolutionary War speech. It’s surprising that it had not. This was Lincoln’s own description, and it is simple and powerful. This final statement in the Address is far from a gentle benediction. It is a steely resolve to continue the fighting, continue the bloodshed, allow more men to die, and to dedicate more cemeteries to the war dead in order to guarantee that the United States will not perish and take freedom along with it. We “highly resolve” to continue the work of this war, knowing that it will not be easy and success is not assured.

Delivering this final line, the president sat down. People in the audience were surprised. They had expected a longer speech—something more along the lines of the “translation” we’ve just provided, something more didactic that pounded points home over and over, and expressed its patriotism in more familiar, jingoistic language. Some felt insulted, and the press reviews were mixed: The Chicago Times said “The cheek of every American must tingle with shame as he reads the silly flat and dishwattery [sic] remarks of the man who has to be pointed out as the President of the United States.” The local Harrisburg Patriot and Union said “…we pass over the silly remarks of the President: for the credit of the nation we are willing that the veil of oblivion shall be dropped over them and that they shall no more be repeated or thought of.”

Part of the problem was that the elder statesman of Massachusetts politics, Edward Everett, had spoken for over two hours in a much more conventional way before Lincoln. Technically, Everett was right to speak longer, as he was on the program to deliver an “oration” while the president was listed as giving only “dedicatory remarks”. It was an age of very long speeches, and the longer the speech, the more seriously the speaker was taken.

But there were many people who realized they had just heard an historic speech. We’ll close with the opinion of the reporter from the Providence Daily Journal who felt the same way we do today after he heard Lincoln speak: “We know not where to look for a more admirable speech than the brief one which the President made…. It is often said that the hardest thing in the world is to make a five minute speech. But could the most elaborate and splendid oration be more beautiful, more touching, more inspiring than those few words of the President?”

I believe the tree trunk mentioned came from the battle of Spotsylvania, more particularly at the “angle.” There is a monument noting where the tree was located at the site. Not much fighting occurred at Appomattox. Best regards, Cliff Norman

LikeLike

Cliff, you are completely right! Not sure how that error got in there, but the correction has been made. Thanks!

LikeLike

Fantastic prose and research. Thanks for the education. Nice work!

LikeLike

First off that picture at the top was not taken during the battle. I took this photo of a re-enactment at Gettysburg. PLEASE REMOVE MY COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL.!!

LikeLike

Removed–we apologize for our error.

LikeLike